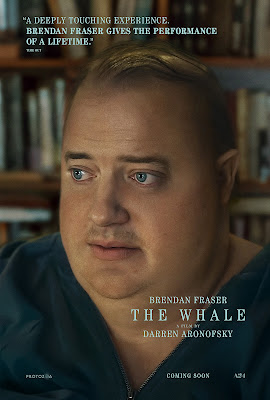

Review | The Whale | 2022

Much has been made about Brendan Fraser's "comeback" in Darren Aronofsky's The Whale. Once a marquee action hero in films like Encino Man, The Mummy, and George of the Jungle, Fraser's career has been mostly quiet for the last decade or so.

Those roles made Fraser a beloved figure for many millennials, and seeing him return to the screen with such a meaty role certainly carries a lot of nostalgia for many - especially after the revelation in a 2018 issue of GQ in which Fraser discussed having been sexually assaulted by the president of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association in 2003 - an event that sent him into a deep depression and caused him to slowly withdraw from Hollywood.His performance in The Whale is certainly a powerful one, but Aronofsky's film is not without its myriad issues - centering around an obese man named Charlie (Fraser) whose weight gain following a tragedy has led him to becoming a shut in, cut off from his family and the rest of the world. His only company is his nurse, Liz (Hong Chau) - whose late brother was Charlie's boyfriend. Charlie spends his days teaching online college courses (his camera turned off because he's embarrassed by his appearance) and slowly eating himself to death as congestive heart failure begins to set in. But despite his blasé attitude toward his own health, he maintains a deeply held belief in essential human goodness, a belief that is put to the test by the arrival of his troubled daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink) and a hapless missionary named Thomas (Ty Simpkins).

The problem here isn't just the depiction of Charlie's weight, its the way in which Aronofsky uses it to constantly undercut his film's own message. The Whale views Charlie as both an object of pity and disgust. We are meant to watch in horror as Charlie devours entire pizza, pouring ranch dressing and covering them in lunch meat before scarfing them down in halves while the soundtrack swells with atonal music that sounds straight out of a horror film. The camera lingers on Fraser's prosthetic-laden body, each reveal of his true size treated as a moment of shock.

The Whale wants us so desperately for us to believe in simple human goodness, to look beyond appearances and even actions and see something beautiful, and yet it treats Fraser's character with such disgust that it is disturbing for all the wrong reasons. Which is a shame because there's some very interesting father/daughter conflict here that is actually quite compelling. Charlie is essentially a broken man who feels as if he's missed out on so much and wants to make good with the one person left he truly loves - but the film simply cannot get past its own fatphobia. The cast does what it can (Fraser, Chau, and Sink are standouts), but the film's contempt for Charlie's size not only leaves a sour taste in the mouth, it muddles its own message. We're supposed to love Charlie despite his size, as if his size is meant to be a barrier to his humanity. We are meant to be repulsed by him but love him anyway - but The Whale could have worked much better had it not used his size as such an object of revulsion. It's good to see Fraser back on the big screen, and he delivers a towering performance here that is bringing him deserving accolades, one only wishes it was in service of a film that sees fat people as something other than objects to be pitied.

Comments