The Ten Best Films of 2021

2021 was a year in flux for the cinematic landscape. With attendance still not at pre-pandemic levels, many films found themselves debuting simultaneously in theaters and via streaming, with home video windows shorter than ever before. It's a double edged sword, with studios taking fewer chances while many films are more accessible than ever, even if their unceremonious streaming debuts don't allow them the same cultural capital as theatrical releases pre-pandemic once had. Still, this has been a tremendous year for film, a year filled with unique works of art destined to stand the test of time. Here are the ten that stuck with me the most.

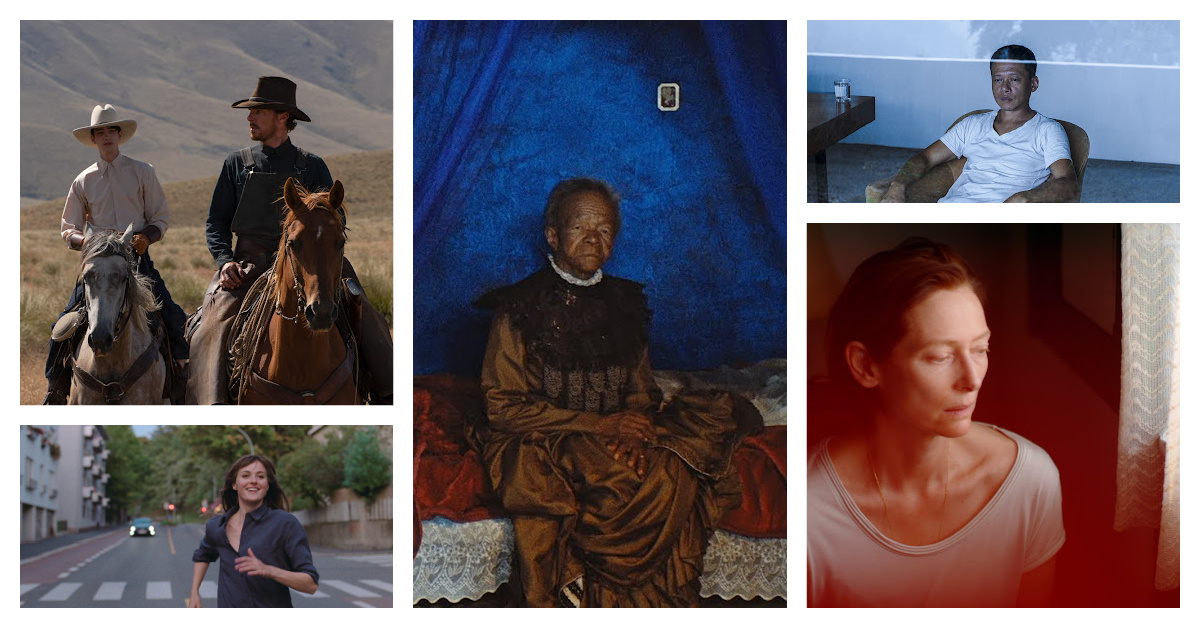

An old woman in Lesotho loses her son to a mining accident, and soon discovers that she will lose her home when her ancestral lands are flooded by a dam being built by South African authorities in Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese's stunning This is Not a Burial, It's a Resurrection.

At once hushed, poetic, and trembling with righteous anger, This is Not a Burial chronicles one woman's radicalization in the face of displacement, turning her son's funeral into a resurrection of her fighting spirit. With nothing left to lose, she decides to stand up against those who would wipe away everything she knows and holds dear. It unfolds like a radical tone poem, a requiem for a way of life coupled with a steely determination to resist the forces of colonialism. The film is deeply entrenched in water and land disputes between South Africa and its native Lesotho, but its message of resistance is universal. Mosese has crafted a work of great and terrible beauty, with a keen sense of time and place and timeless sense of justice. No other film felt more deeply radical or singularly enrapturing as this one.

To watch a film by Apichatpong Weerasethakul is to enter a truly singular cinematic realm. If film is like a drug, as Weerasethakul once proclaimed, then his films are a strong and heady batch indeed, capable of penetrating realms of consciousness that seemingly exist both within and apart from our reality.

His latest film, Memoria, is as inscrutable and mystifying as anything in his filmography, a film as much about alienation as it is discovering connections in unexpected places. Here is a Thai filmmaker directing a Scottish actress in a Colombian production - these elements do not seem to easily mesh and yet somehow they create something uniquely wondrous and quietly exhilarating. Everyone here is a stranger in a strange land, but rather than exoticize Colombia, Weerasethakul uses its remote backdrop and liminal spaces as a staging ground to explore human alienation in ways that seem to echo through the ages, rattling around in our minds like a mysterious sound reverberating from the vastness of time and space. It's nearly impossible to adequately describe Memoria in words, as it's the kind of film that simply must be experienced.

What to make of Jane Campion's The Power of the Dog, a thorny, mighty piece of cinema that seems cleaved directly from the earth? It's a monumental achievement that seems at once classical and thrillingly modern, a deeply introspective exploration of American masculine myth making through the lens of that most American of genres, the western.

Working from the 1967 novel by Thomas Savage, Campion masterfully evokes the weakness underlying traditional masculinity, where fear and insecurity are masked by petty bullying and performative posturing. It's a punishing but deeply rewarding film, like a negative inverse of Brokeback Mountain, a punch drunk erotic fever dream that probes the depths of toxic masculinity to find strength in something fare more delicate. The Power of the Dog is an intoxicating and uneasy work, a consistently prickly and turbulent film that alternates between great and terrible beauty and the rot at the core of American myth-making. It's John Ford by way Pier Paolo Pasolini, at once classical and revisionist, seductive and terrifying, a giant of modern cinema reiterating her mastery on a grandly intimate canvas, giving us a queering of the American west that feels both inevitable and severely overdue.

I felt this film in my bones like nothing else this year. The Worst Person in the World is perhaps one of the most indelible portrayals of millennial angst and ennui that I've ever seen on screen. Joachim Trier really digs into the messiness of life here - fuck ups and triumphs, meeting the right person at the wrong time, the wrong person at the right time, conflicting desires and goals and how relationships ebb and flow. It's all there, and it's so, so real.

We cling to the past through nostalgia because the future is bleak. We search for answers where there are none, believing we're helping. But above all it's a reminder to extend ourselves a little grace. We're all just trying to get by. Sometimes we're happy, sometimes we're petty and cruel, sometimes we say things we don't mean. We hurt the people we love. We laugh. We heal. We learn nothing and do it again. God this movie hurt in the most beautiful ways. In a world where empty nostalgia is raking in huge box office profits, The Worst Person in the World dares to examine the pain that keeps us stuck in the past.

Two men, one a chronically ill and chronically single man, the other a young Laotian immigrant, go about their days alone before meeting in a uniquely beautiful moment of sexual and physical healing that forever changes the direction of their lives. Tsai Ming-Liang's brand of slow cinema is so deceptively simple, seemingly meandering along at a glacial pace before almost imperceptibly revealing its emotional core. The moment shared between the two men shatters the delicate emotional balance of Tsai's carefully constructed narrative, so that something as unassuming as a soft tune plucked out on a music box can have powerful emotional ramifications that reverberate out through the rest of the seemingly mundane moments.

Barely a word is spoken for the entirety of Days' 130 minutes, lulling the audience into a kind of routine, so that the moment the routine is interrupted we feel it in our souls. Days is not only the most romantic film of the year, it's one of the most disarmingly emotional, a work of almost limitless beauty that only a true master could have conjured. The silence speaks volumes here, leading to one of the most quietly shattering finales in recent memory - a moment of such boundless tenderness that is some of the most graceful filmmaking of Tsai's career.

In her follow up to her arthouse hit, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Céline Sciamma turns her eye toward a different kind of love in the tender fantasy, Petite Maman. While cleaning out her late grandmother's house with her mother, eight-year-old Nelly meets the younger version of her mother out in the forest, forging an unlikely bond between mother and daughter as children that helps the two of them finally connect and understand each other.

At only 72 minutes long, Petite Maman unfolds like a short fairy tale, but it packs a huge emotional wallop. Rarely has a film about love and loss felt so profoundly intimate, as it slowly peels back the layers of each other's pain by allowing mother and daughter to meet on their own levels. It's a hushed, haunted ghost story of two souls haunted by the past, united in mourning, and at last seeing each other through in a unique and magical place. This is Sciamma's own Miyazaki film, short, sweet, and profound, a lovely examination of motherhood and childhood that hits hard and fast.

Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch is often described as an "ode tp journalism," and indeed the film takes a kind of wistful look at a certain era of long form writing that allowed writers to examine esoteric human interest stories that spoke to them on an emotional level, but ultimately it's not just about the profession of journalism as it is so much the singular artistic possibilities of the written word.

It doesn't wear its heart on its sleeve like The Grand Budapest Hotel or The Royal Tenenbaums (perhaps his two finest works), but like the intrepid reporters who make up its kooky cast, it arrives at its lugubrious destination in curious and often hilarious ways, but the final emotional doesn't fully resonate until long after the credits have rolled. It's a wonderfully strange achievement, as much a love letter to the written word as a sly tweaking of its pretensions, a layered and mannered collection of droll bon mots and forlorn recollections whose observations and delights aren't always laying directly on the surface. Like any good story, they're layered throughout like breadcrumbs for the viewer (or reader) to discover along the way, and it isn't until they're all collected that the true breadth of its impact reveals itself. The French Dispatch is as sad and thoughtful and funny as anything Anderson has ever made, a sparkling gem in the illustrious career of a filmmaker who refuses to be pinned down, even when everyone thinks they have him figured out.

A kind of miraculous exploration of random romantic connection and human absurdity, What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? is perhaps one of the year's most truly singular cinematic experiences. I was skeptical of this at first; its rhythms are strange, its story almost inscrutable, and I was about to write it off as altogether too clever for its own good. But about halfway through something clicked and I fell under its unique spell.

The story is, of course, beside the point. Koberidze is far more interested in the random beauty at his characters' periphery. It's a cinematic invitation to stop and smell the roses - and it's unlike anything I've ever seen; trafficking in a kind of mundane, observational magical realism that feels part Manoel de Oliveira, part Roy Andersson. It breaks the fourth wall repeatedly, openly acknowledges the absurdity of its story, and consistently questions the purpose of the whole affair. And by the end it's lulled us into a kind of bemused reverie, almost in disbelief that not only does this work - it's actually great. It takes a while to settle into but it's well worth the effort. It's so wholly it's own thing that it's nigh on impossible not to be charmed by it's almost childlike wonder at the simple beauty that surrounds us, even in the darkest times.

Following up her 2016 horror film Raw, Julia Ducournau seems likely to inherit David Cronenberg's throne as master of cinematic body horror with her latest film, the Palme d'Or winning Titane. Centering around a young woman whose life is forever changed by a tragic car accident, the film follows her as an adult on the run for murder after being impregnated by a car. Posing as a missing boy, she finds herself all but adopted by a lonely man yearning for the return of his beloved son.

It is, perhaps, one of 2021's most unforgettable cinematic experiences, an endlessly fascinating exploration of gender and sexuality about a woman who does not feel at home in her own body, culminating in some of the most visceral and haunting images captured on screen this year. Ducournau masterfully guides us through some truly out there science fiction, while keeping the action grounded in searing human emotion, buoyed by some of the year's most indelible performances by Agathe Rousselle and Vincent Lindon. It's a film that truly must be seen to be believed.

Helen Keller is one of those historical figures whose legacy has been so white washed by history that it has become a kind of cornerstone of warm and fuzzy American "triumph over adversity" mythology while bearing little resemblance to who Keller actually was and what she stood for. Keller was deeply involved in radical left wing politics throughout her life, aided in no small part by her teacher, Anne Sullivan, often acting as her guardian and interpreter.

As there is no film footage of Keller's speeches, Gianvito is forced to rely on a series of photographs and images of Keller's surroundings to piece together the essence of her life, of which her words are the glue. The effect is nothing short of spellbinding, a radical documentary about a radical figure whose true legacy has been sanitized into an American bootstrap myth that undercuts its subject's work on behalf of the marginalized, work that made her more than a few powerful enemies during her lifetime. It is an injustice of breathtaking performances that her voice has been stolen from her once again by the pages of history, but Her Socialist Smile boldly reclaims her legacy so that when we finally do hear her actual voice, the effect is galvanizing. It's the year's finest documentary, and Keller's true work has never felt more urgent or more essential than it does now.

Comments