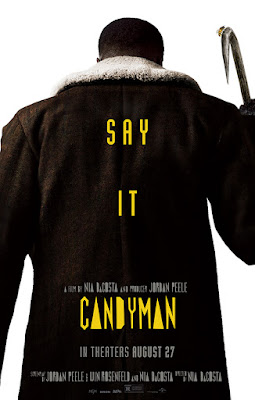

Review | Candyman | 2021

Nia DaCosta's legacy sequel to the influential slasher film, Candyman (1992), takes a lot of the original film's subtext and makes it text, reimagining the titular murderous spirit as a symbol of black trauma and rage, a vengeful judgment against white supremacy's brutal legacy.

Candyman (2021) acknowledges the events of the original film, but one need not have seen the 1992 film in order to understand what's going on here. DaCosta updates the idea and continues the story without trafficking in a phony sense of nostalgia. Instead, she builds upon what is already there, updating the concept for an era in which Black Lives Matter continues to be a resonant mantra and debates about "critical race theory" haver permeated the national political landscape. Here, Candyman isn't just an urban legend, a children's fairy tale based on the tale of a black man who was murdered by a mob in the 1890s for falling involve with a white woman. Here, Candyman is, as one character puts it, the entire swarm, a howl of rage at historical injustice whose power only grows with each black person murdered at the hands of lynch mobs and police who have terrorized the housing project of Cabrini Green for generations. Candyman is, to put it simply, generational black trauma personified.

Cabrini Green has long sense been gentrified, the remaining tenements now mostly abandoned and forgotten by as upscale apartments and art galleries have made it a hot commodity with skyrocketing property values, the former tenants now displaced. Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is an artist living with his girlfriend, Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris), in a high-rise apartment overlooking the old housing projects. Anthony is looking for inspiration for his new gallery installation, and finds it in the Candyman legend, inadvertently resurrecting the vengeful spirit (Tony Todd, reprising his role from the original film) from his eternal slumber. As the body count grows, Anthony becomes more and more obsessed with Candyman, and soon he and those he loves are forced to grapple with his bloody legacy, and how they are inexorably connected.

Many black critics have pointed out the use of black suffering as horror fodder in films such as Antebellum, and while that discussion has surely been had regarding Candyman, DaCosta actually takes the time to grapple with the idea of how art can both heal and exacerbate trauma. By making her protagonist an artist, one trying to grapple with the violence he's seeing, it's almost as if DaCosta herself is wrestling with how to depict those violence and pain, and how her efforts can both exacerbate and help to acknowledge them. Turning Candyman into a kind of folk hero is a stroke of genius, a ghostly crusader fighting injustice from beyond the grave. While it often paints with an overly broad brush, DaCosta has created a beautifully idiosyncratic and haunting film, a thing of rare and terrible beauty that is at once a singular and wonderfully off-kilter work. Both Abdul-Mateen and Parris are terrific in the leading roles, and composer Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe admirably steps into Philip Glass' massive shoes, evoking his minimalist circular rhythms to achieve something both beautiful and terrifying.

Not every part of Candyman lands, but that's part of what make it so fascinating. You can feel DaCosta grappling with the film's thorny thematic content, probing, exploring, and experimenting. "Say his name," a now familiar mantra for the Black Lives Matter movement, becomes a similar rallying cry for Candyman here, because there is power and agency in remembrance. I will leave Candyman's success on that front to more learned critics of color whose experiences are imbedded in the film's depiction of trauma, but what is undeniable is that DaCosta seems to be working through these ideas herself right before our eyes. And the results are mesmerizing, terrifying, and strangely cathartic - messy, passionate, and gloriously inventive in all the right ways.

Comments