Blu-Ray Review | Two Senegalese Classics from Criterion

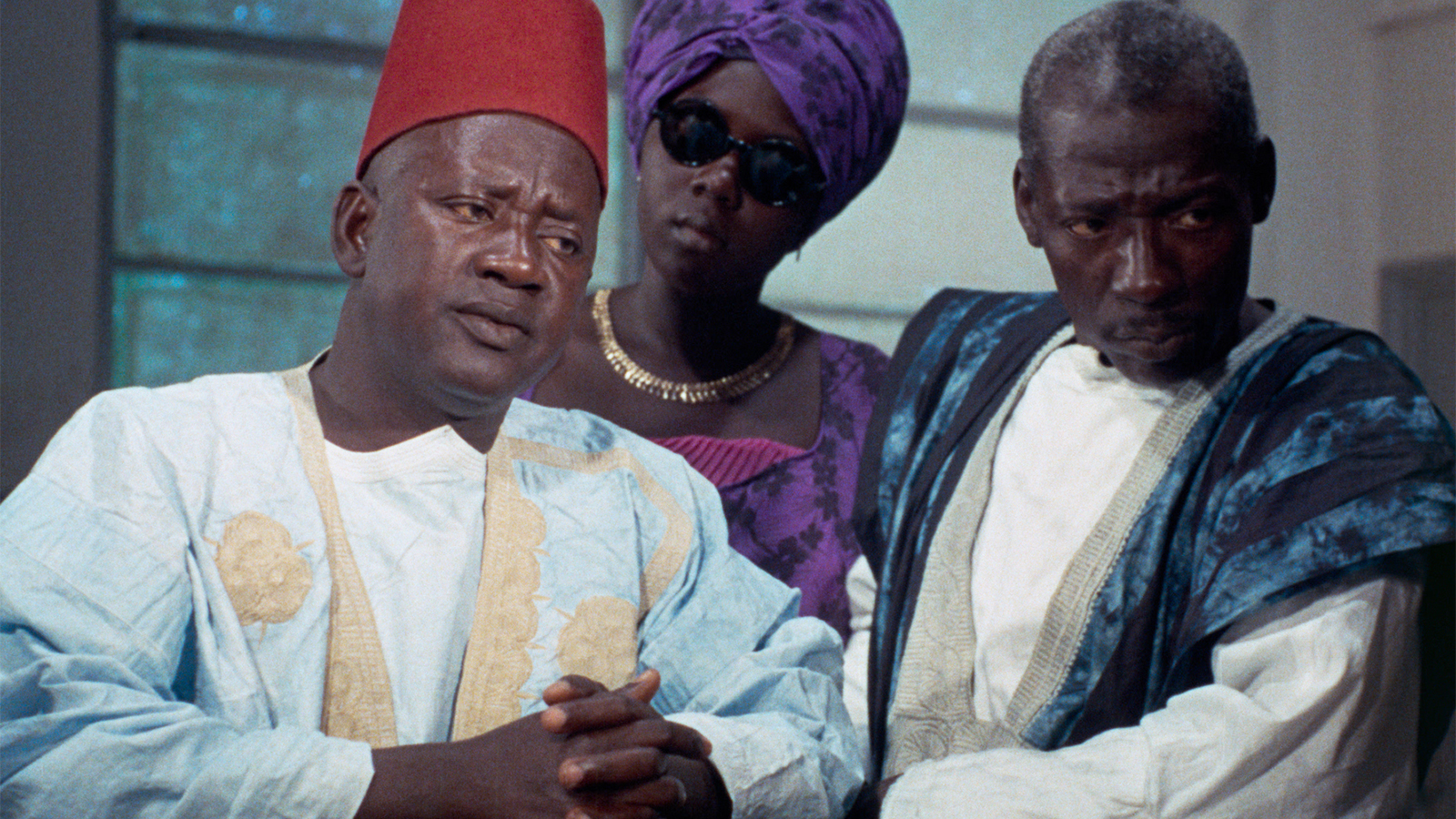

A scene from MANDABI. Courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

MANDABI (Ousmane Sembène, 1968)

Notable for being the first film ever to be filmed in an African language, Ousmane Sembène's Mandabi (The Money Order) is part grim satire, part absurdist tragedy; a Sisyphean portrait of a poor man's struggle to exist in a world designed to benefit the wealthy and the elite. Centering around Ibrahima Dieng (Makhouredia Gueye), an unemployed man whose nephew sends him a 25,000 franc money order from Paris to distribute amongst the family, the film not only examines the way in which money changes human behavior, it eviscerates the absurdity of the bureaucratic state. When Dieng's friends and neighbors learn of the money order, the immediately descend on him to ask for money, but he finds himself unable to cash the money order since he doesn't have ID, a record of his birth, or the ability to read the agreements in order to get those documents. By the time he's finished, he's all but spent the entire money order just to cash it, ending up worse off than he was at the beginning of the film when he thought fortune had at last smiled upon him.

Sembène was an intensely political filmmaker, and while he pulled his focus away from French colonialism after his previous film, the pointedly anti-colonial Black Girl, to take aim at, as he put it in a 1969 interview, "the dictatorship of the bourgeoise over the people." In that regard, Mandabi is perhaps one of the greatest communist films of all time, disguising beneath its absurdist humor a sense of righteous fury at the government roadblocks seemingly set up specifically to keep the poor in their place. Indeed, the very existence of Mandabi is something of a protest. By shooting the film in Wolof, rather than the customary French, Sembène is declaring that this is a Senegalese film made by and for Senegalese people. And although funders demanded that Sembène put together a French language version simultaneously, it is the Wolof version that has endured, giving a voice to African cinema that had not previously been heard. Senegal has an especially rich cinematic tradition, giving rise to Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty (Touki Bouki), his niece, Mati Diop (Atlantics), Safi Faye (Kaddu Beykat), among many others. While the specter of French colonialism hangs over many of the nation's defining works, there is often a deeply humane political sensibility at play that speaks their filmmakers' leftist worldviews, tackling the universally corrupting influence of money whether it be the promises of riches or how they affect human behavior. One might mistake Mandabi for a religious parable centering around a modern day Job, but that's what makes Sembène's communist worldview so bracing - the tone may be bitter, but there's a deep and abiding humanity at its core that is at once universally appealing and difficult to forget.

GRADE - ★★★★ (out of four)

|

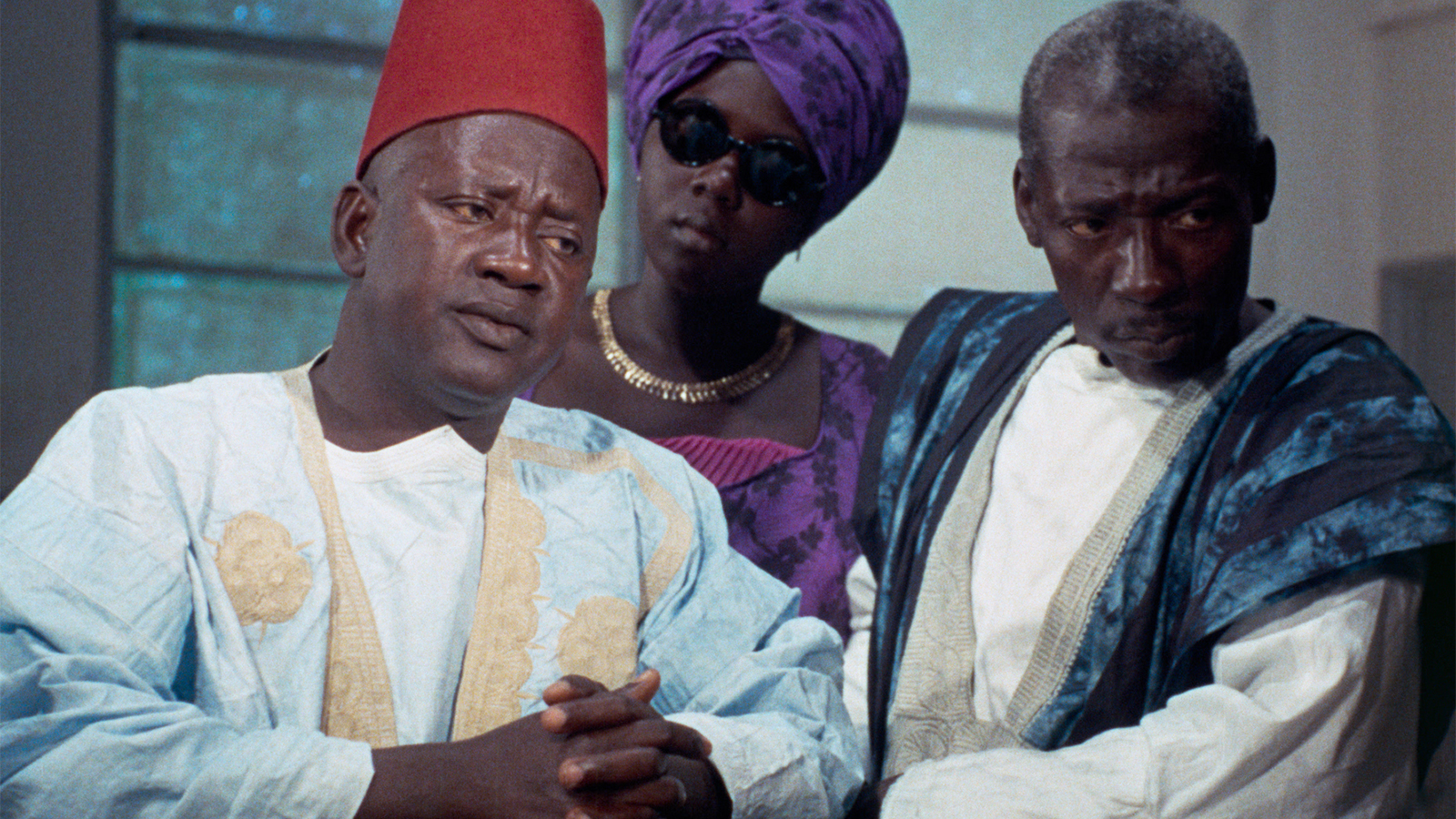

| A scene from TOUKI BOUKI. Courtesy of the Criterion Collection. |

TOUKI BOUKI (Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973)

I was first introduced to Djibril Diop Mambéty's dazzling Touki Bouki (Journey of the Hyena) through the Criterion Collection's first box set from Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project. Watching Scorsese's introduction (once again included in this new standalone release), it's nearly impossible not to get caught up in his clear love and enthusiasm for this film, and it lives up to his effusive praise in every way. More abstract and perhaps more impressionistic than the socialist realism of the films of his contemporary, Ousmane Sembène, the films of Djibril Diop Mambéty have an almost otherworldly quality to them, fully part of the Senegalese landscape in which they take place, yet existing on a kind of dreamlike plane, alive with the sights and especially the sounds their characters encounter.

Like Sembène, however, Mambéty's films are also deeply political, often informed by the effects of French colonialism on his native Senegal. Touki Bouki follows the misadventures of a young couple who long to leave their impoverished existence in Senegal for the promise of a better life in France, a journey that is increasingly thwarted by seemingly cosmic circumstances. Their journey across Senegal on the back of a motorcycle mounted with cattle horns becomes a kind of modern day Odyssey, often accompanied by the cheery strains of Josephine Baker's "Paris, Paris," whose stark dichotomy with the events portrayed on screen strikes an absurdly comical commentary on the promise of riches that await them in France. Sound often played an key role in Mambéty's work, reportedly because his youthful trips to the cinema were made outside the gates where he could only hear the films, because he could not afford the cost of a ticket, and Touki Bouki s use of music is perhaps some of the most indelible in cinema history. It's so rich, so memorable, and so perfectly in tune with the film's thematic content - actively deepening the absurdity of the French promise in contrast with the poverty left behind by French influence in post-colonial Senegal. Mambéty made precious few films in his long career, directing only two features and five shorts between 1969 and 1999, but Touki Bouki remains his masterpiece - a mischievous yet haunted exploration of post-independence Senegal that deftly evokes the futility placing ones dreams in the the ideal of their formal colonizers. Where Sembène sought cold, hard truth, Mambéty sought emotional honesty, crafting a visceral experience striking visuals and daring aural soundscapes that sought to make sense of a world that no longer did.

Comments