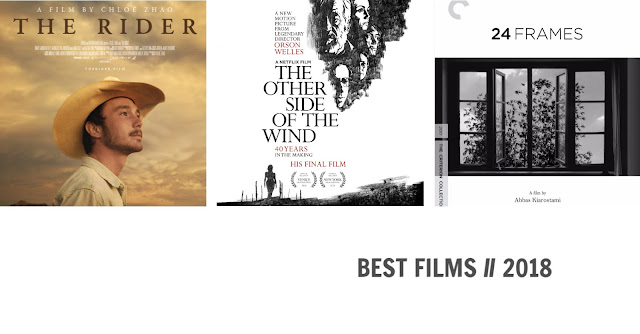

Year in Review | The Best Films of 2018

1 | THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND (Orson Welles, USA)

A film seemingly from beyond the grave, Orson Welles' The Other Side of the Wind began production 40 years ago, and became the legendary filmmaker's final obsession, a project decades in the making that was never completed before his death. Finally assembled by Peter Bogdanovich , Welles' final film can finally be recognized as the masterpiece that it is. Here, a man who started his career making avant-garde silent shorts and radio dramas creates one of the most brazenly modern films of his career, a work of experimental cinema that takes stock of the industry as Welles saw it - from the New Hollywood Cinema of Scorsese, De Palma, and Coppola, to the European art house cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni (mercilessly lampooned in Hannaford's film-within-a-film). This is cinema as voyeurism, for both the filmmaker and the audience. Is cinema a means to an end or simply an end? A journey or a destination? A penetrative act or a reflective act? Here, Welles dismantles the male gaze, the camera as a phallus, positioning cinema as an act of rape that destroys that which it seeks to exalt. It is a daring, reckless, uncompromising film that has risen like a phoenix from the ashes to take its place in the pantheon of great things - the final film of an American master who, 33 years after his death, has shown the world that he is just as vital and brilliant as ever.

2 | THE RIDER (Chloé Zhao, USA)

Chloé Zhao's sophomore feature is a rough-hewn elegy for the American west and the archetypal masculine mystique of the cowboy. At a time when toxic masculinity and its devastating effects dominate the news, Zhao, who was born in China before immigrating to the United States to study political science at Mount Holyoke College, has crafted something deeply special; a film that offers more insight into wounded masculinity than just about anything else in recent memory. Forget "Hillbilly Elegy,' The Rider is the profound exploration of rural ennui we need.

Through the achingly authentic performance of her non-professional lead and some truly breathtaking cinematography by Joshua James Richards, The Rider paints a heartbreaking portrait of a generation of young men searching for their identity, set against the backdrop of the fading American West. It's a delicate and tremulous thing, at once confident and gentle, lyrically composed yet as stoic as the American masculine ideal it so carefully deconstructs. This is a major film by a major filmmaker, a stirring and compelling search for the idea of the American man at a time when toxic masculinity has brought us so much ill through its anger and fragility. Zhao seeks to find another path forward through the myths of our past, and the results are nothing short of stunning.

3 | 24 FRAMES (Abbas Kiarostami, France)

Jean-Luc Godard once said that "cinema is truth at 24 frames per second." In Abbas Kiarostami's dazzlingly experimental 24 Frames, the final film completed before his death, the revered Iranian filmmaker explores the very idea of truth in art and cinema through a series of vignettes, or "frames." Each frame is a still image, a painting or photograph, brought to life through computer animation in order to examine what happened before and after the image was captured.

These images, Kiarostami posits, only capture a moment in time and therefore tell an incomplete story. They are, inherently, false. What follows is a bold, probing work that questions and explore the very idea of cinema and truth itself. Each frame is a story unto itself - sometimes playful, sometimes tragic, each looking at works of art in new and exciting ways, like an art gallery come to life through the magic of the silver screen. Kiarostami uses sound to suggest action happening outside the frame, the images extending into infinity beyond the bounds of art and film and into the world around us. It is no mistake that there are 24 frames in total - most films are projected at 24 frames per second. And in this, his final artistic statement to the world, Kiarostami has crafted a haunting and meditative examination of the very nature of the medium to which he devoted his life - one final masterpiece to question and challenge what is possible through art.

4 | LET THE SUNSHINE IN (Claire Denis, France)

Based upon Roland Barthes' "A Lover's Discourse: Fragments," Let the Sunshine In finds Claire Denis directing with a kind of sardonic distance - at once warm and bitter, joyous and stinging - each moment of mirth almost negated by the nagging sense that Isabelle is making the same mistakes over and over again. No one grows, no questions are answered, there is no clear satisfying arc for Isabelle, and therein lies the film's inherent tragedy. Binoche is luminous as always, a woman who, through multiple romantic and sexual encounters seeks fulfilment through a man rather than through herself, refusing to "let the sunshine in" and be happy with herself. It is a tragedy played out across Binoche's face in the final moments of the film, the dawning wonder in her eyes as she begins to fall for a charming charlatan's snake-oil pitch just as piercing and heartbreaking as Timotheé Chalamet's tears over the end credits of Call Me By Your Name. It's Denis' most emotionally wrenching work since 35 Shots of Rum, a beautifully understated and often transcendent exploration of the painful and bittersweet contradictions of the human heart.5 | FIRST MAN (Damien Chazelle, USA)

Audiences going into First Man expecting an epic retelling of Neil Armstrong's iconic walk on the moon were instead treated to an introspective character study about grief and loss. This may have contributed in part to the fact that the film underperformed at the box office and faded from the Oscar conversation before it ever got off the ground, but Damien Chazelle's follow-up to his Oscar-winning musical, La La Land, boldly looks inward even as its protagonist adventures outward, examining the deep personal cost of exploration and America's pioneering spirit. Chazelle takes an epic tale and brings it down to earth, making the monumental personal and the historic immediate. Rarely are films of this scale so deeply intimate and yet so grandly realized. No other film this year was so wholly immersive or more immaculately crafted.6 | HAPPY AS LAZZARO (Alice Rohrwacher, Italy)

Italian filmmaker Alice Rohrwacher infuses her enigmatic fable with the wit of Hal Ashby, the religious gravity of Carl Dreyer, and the medieval absurdity of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Elements such as time and place have little meaning, in fact Happy as Lazzaro feels more like a dream, untethered to such earthly concerns, shot in beautifully hazy 16mm by Hélène Louvart. Seasons can change from shot to shot, the sharecroppers' milieu shifts from that of an 19th century farm to modern day. Where and when the film takes place is fluid. What matters is Lazzaro, our Christ-like hero, who serves as our surrogate in this world of injustice and pain. Lazzaro is seemingly too good for this world - pure beyond understanding. Here Rohrwacher grapples with faith and class struggles in mysterious and fascinating ways - posing the haunting question; would we recognize the face of God if we saw it? Rohrwacher reaches out and captures a spark of the divine, something intangible and cryptic yet wholly wondrous, even miraculous - an enchanting modern parable of simple goodness destroyed by a world that can't possibly understand it that somehow still manages to provide a glimmer of hope for a better future.7 | EL MAR LA MAR (J.P. Sniadecki & Joshua Bonnetta, USA)

8 | ZAMA (Lucretia Martel, Argentina)

Ostensibly a film about the hell of middle management, Lucretia Martel's satirical 17th century drama examines the existential trials and tribulations of a mid-ranking Spanish official stationed on a remote island patiently awaiting a transfer to Buenos Aires that will never come. Trapped in a kind of purgatory of his own making, Don Diego de Zama languishes away in an increasingly disheveled wig, attempting to make sense of his mostly pointless colonial duties. He becomes a conduit for Martel's scathingly hilarious portrait of the folly of colonialism - featuring a never-ending parade of self-important white people in laughably impractical costumes in the sweltering heat, attempting to subjugate a culture they will never understand. Martel's brilliant use of sound suggests Zama's creeping madness and unravelling mental state, a sense of spiritual petrification from which there is no escape. It's as if the spirit of Luis Buñuel has settled upon the film, recalling the surrealist satire of films like The Exterminating Angel, where characters become trapped in existential webs they've spun for themselves, unable and unwilling to understand that they are the source of their own misery.9 | IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK (Barry Jenkins, USA)

Somewhere amid the weeping strings and soaring saxophones of Nicholas Britell’s sublime score, Barry Jenkins' If Beale Street Could Talk touches on some essential truth about what it feels like to fall in love. It’s as if the film is on the brink of tears it’s entire run time, its heart full with the beauty of life while at the same time mourning for the wholesale destruction of black lives at the altar of white supremacy. Adapted from the novel by the great James Baldwin, it is at once a devastating indictment of an America that refuses to acknowledge its roots in white privilege and the subjugation or black bodies, and a celebration of the tremulous and often breathtaking nature of love itself. Quite the achievement indeed, but Jenkins balances it so well, placing his characters in the center of the frame, eyes staring longingly into the camera as if they’re staring into our very souls. He places us in the film, creating an immersive and enrapturing experience akin to falling in love for the first time. A film of ebullient joy and exquisite sadness.

10 | SUPPORT THE GIRLS (Andrew Bujalski, USA)

“For mothers” reads the post-script of Andrew Bujalski's Support the Girls, a wise, wonderful, and altogether miraculous film about the long-suffering manager of a knock-off Hooters sports bar dealing with the seemingly never-ending crises of middle management. For Bujalski, whose trademark brand of improvisational realism first brought the term "mumblecore" into the popular lexicon, Support the Girls is perhaps his most formal work yet. But never once does he sacrifice verisimilitude for structural precision. Support the Girls is a warm, funny, sublimely entertaining film, anchored by a soulful performance by Regina Hall, whose smiling face barely hides the weariness underneath. It's one of the understated wonders of the year in film, a small-scale miracle that peels back the smiling, attractive facade of the American service industry and reveals the blood, sweat, and tears that keep the fantasy going.11 | SHOPLIFTERS (Hirokazu Kore-eda, Japan)

What is family? There is seemingly no better filmmaker working today to answer that question that Hirokazu Kore-eda, whose family dramas have often been compared to those of the great Yasujiro Ozu. His Palme D'Or wining Shoplifters takes some of the director's favorite themes and looks at them from a new angle, through the eyes of an unconventional family who live off of stealing from others, whose penchant for taking what does not belong to them becomes ever more apparent as the film goes on. Family is what we make it, and in Shoplifters Hirokazu paints a heartbreaking portrait of a family like no other, built from scratch and forged by fire. It leaves an indelible impression, slowly building to an unforgettable emotional crescendo that is so expertly devised that we almost don't see it coming. Like Hirokazu's best work, it is quiet, hushed, and often unassuming, but lands with power of an earthquake.12 | DID YOU WONDER WHO FIRED THE GUN? (Travis Wilkerson, USA)

In 1946, Travis Wilkerson's great grandfather murdered a black man named Bill Spann in his store and got away with it. It was a source of pride for SE Branch all his life - he had gunned down a black man in cold blood and walked away scot-free. Wilkerson, a radical political filmmaker and documentarian, delves into his family's dark past in his new film, Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun?, a chilling and courageous act of self-reflection that refuses any attempt to atone for the past, instead examining how he himself is complicit in a racist past.

This is a radical sledgehammer of a film, a ferocious work of avant-garde essay filmmaking that dares to hold a mirror up to a white audience and demand that we examine our own complicity in a racist society. How can we ever fix a system when the very idea of whiteness itself is the problem? Has the institution of whiteness so entrenched itself in American life that we can never actually move forward without starting over to fix the head start we've given ourselves? What Wilkerson has achieved here is truly stunning, a radical act of allyship in which a white filmmaker grapples with his own past, and his place in a world built by racist ancestors. It's a deep examination of privilege that refuses to let its audience off the hook.

13 | PROTOTYPE (Blake Williams, Canada)

A bold experimental work of avant-garde cinema in the tradition of the early silent surrealists and dadaists such as Luis Bunuel and Man Ray, Black Williams' PROTOTYPE is a mesmerizing, immersive experience unlike anything else. It feels like a journey into another realm of consciousness, exploring the boundaries of the cinematic medium and questioning what's possible. Williams throws the rulebook out the window and starts from scratch, creating a film that is at once a searing exploration of our own relationship to visual media and an audacious reinvention of the cinematic language. Just as Godard bid farewell to the old ways of artistic expression in Goodbye to Language, with its equally brash use of 3D, PROTOTYPE takes those ideas and transforms them once again into an electrifying, uncompromising redefinition of what it means to be a film.There's never been a film (or series of films) quite like Patrick Wang's A Bread Factory. Essentially one film told in two parts, Part One: For the Sake of Gold, and Part Two: Walk with Me a While, A Bread Factory examines the plight of a small-town arts center about to be gentrified out of existence by a foreign conglomerate. A Bread Factory is a warm-hearted ode to local arts programs, how they serve not only as a place of belonging for everyone in the community, but as an outlet for people of all ages to explore themselves. Over the course of two films, Wang examines the Bread Factory's impact on its community, and the community's impact on the Bread Factory and its proprietors.

They're two lovely, altogether wonderful films that find a deep humanity in their subjects. And yet there's a kind of sadness that hangs over these films, a kind of mourning for the role of money in the arts, a necessary evil they both rely on and are torn down by. In the end, the quality of the work matters little in the face of public indifference or lack of funding, and that's the inherent tragedy at the core of both films. Passion can only go so far, but sometimes that passion is worth more than anything money can buy. In A Bread Factory that passion bleeds through every frame - it's an endlessly charming labor of love that firmly establishes Wang as one of the most unique and vital voices in American independent cinema.

15 | DEAD SOULS (Wang Bing, France)

The nearly 9-hour running time of Wang Bing's monumental documentary, Dead Souls, may be daunting, and will likely scare away many audience members before they ever walk in the door; but there are few cinematic experiences in 2018 as powerful or as essential as Wang's devastating examination of the Chinese re-education camps that were the result of Chairman Mao Zedong's cultural revolution in the 1950s. This is a monumental work, recalling Claude Lanzmann's Shoah in its expansive dedication to documenting such large-scale human tragedy. Wang channels the voices of both the living and the dead into a stinging indictment of political oppression and human cruelty, crafting a trenchant and often painful portrait of a largely forgotten atrocity. Dead Souls is not a film for the faint of heart, but no other film this year felt more vital, immediate, or audacious, earning every minute of its gargantuan runtime with gripping, deeply compassionate efficiency.

Comments