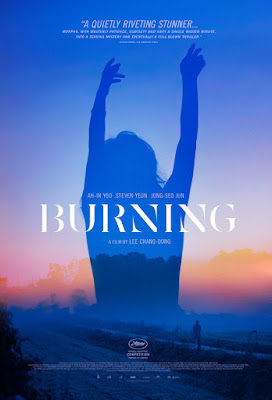

Review | Burning | 2018

Much like his last two films, Secret Sunshine (2007) and Poetry (2011), both lyrical examinations of women attempting to cope with tragedy, Korean filmmaker Lee Chang-Dong's Burning is a kind of anti-mystery, a film where murder is the catalyst for a much larger exploration of Korean society.

Unlike those previous films, however, the woman at the center of the story is not the protagonist, rather the almost abstract projection of male fantasy for the film's two male leads - Jongsu (Yoo Ah-in) a smitten delivery boy with whom she grew up, and Ben (Steven Yeun), the enigmatic new boyfriend she picks up on a spontaneous trip to Africa. Haemi (Jun Jong-seo) exists as a kind of blank slate on which the two men project their fantasies and ideals. For Jongsu, she is the "manic pixie dream-girl" he has been in love with his entire life, having grown up nearby idolizing her from afar. For Ben, she is a kind of toy, something to be picked up and thrown away on a whim. Jongsu is immediately suspicious of Ben's motives. Heartbroken by her seeming rejection of him after a mid-afternoon tryst before she jets off to Africa on a journey of self-exploration, Jongsu spends months visiting her apartment to feed her cat and masturbate on her bed, all the while constructing a vision of Haemi that doesn't really exist.When Ben confides to Jongsu one night that he burns down greenhouses as a hobby (while Haemi dances naked in the sunset before them, a kind of embodiment of the fantasy the two men have constructed between them, sublimely and portentously scored to Miles Davis jazzy improvisations from Elevator to the Gallows), it isn't clear if he's speaking literally or metaphorically. This is where Lee starts building his expertly crafted mystery, because soon after Haemi disappears, and Jongsu seems to be the only one who notices or cares. Ben, intoning "you can make it disappear as if it never existed" with an almost detached nonchalance about his burned down greenhouses, seems the most likely suspect. But as Jongsu attempts to track her down, he uncovers a series of lies and deceptions that lead him to dubious conclusions, and leave the audience questioning whether Haemi existed in the first place, or if she was some sort of male fantasy, a ghost being chased by horny and entitled young men.

Ben is almost a caricature of the entitled rich, while Jongsu is a kind of shiftless man-child for whom women are more sexual objects than real people, fodder for masturbatory fantasies rather than actual relationships. Lee shoots the film mostly from Jongsu's point of view, placing us in the hands of an unreliable narrator we're not sure we can trust. Is Haemi dead? Is Ben a murderer? Or did Haemi (or at least Jongsu's version of Haemi) ever exist at all? Burning is a hazy, haunted evocation of a trio of lost souls trying to navigate life, trying (and often failing) to craft identities for themselves when they don't really know who they are themselves. Haemi has fallen into a trap of credit card debt, a problem among many Korean women trying to "keep up with the Joneses," while Ben and Jongsu embody twin pillars of male entitlement and rage.

That male rage is what percolates so darkly at the heart of Burning. Every frame seems to vibrate with it, clouding not only the characters' judgment but the perception of the audience as well. It obscures everything, from character motives to the truth itself, leaving the audience to feel its way through the fog. It's a disorienting, bracing, wholly exhilarating experience, filled with an unnerving and often eerie sense of impending doom that can't be stopped. Lee purposefully leaves the audience questioning its own eyes, positioning the film squarely in a moral gray area that forces the audience to question and evaluate itself. At one point the film's working title was "Project Rage" (it's loosely based on the short story, "Barn Burning" by Haruki Murakami), and indeed every frame seems to be saturated with anger. Yet that anger is always bubbling beneath the surface, seething and churning in a dark maelstrom that only occasionally breaks the surface. That hidden nature of its anger makes the film all the more disturbing. In a world of mass shootings almost exclusively perpetrated by angry young men, it is the rage you cannot see that is the most frightening, and the hardest to combat until it comes bursting through when something finally snaps. In Lee's haunted world we know a snap is coming, and when it finally arrives we're left with a sense of disquiet. We either just witnessed a moment of justice, or an act of cold-blooded cruelty. But what is most disturbing is Burning's final and most troubling query - is there really a difference?

Comments