From the Repertory | October 7, 2017

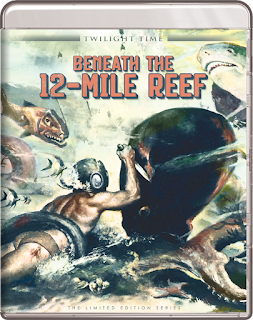

BENEATH THE 12-MILE REEF (1953, Twilight Time)

Robert D. Webb's Beneath the 12-Mile Reef was either the second or third filmed shot in CinemaScope, depending on who you ask. Either way, this early widescreen film was a hit for 20th Century Fox, most likely because of the novelty of its cinematography. The film itself is a bit of a slog, a dry Romeo & Juliet riff set amid two warring families of sponge-divers. Who knew that the world of sponge-diving was so cutthroat?

It's interesting that even in 1953, there were themes of environmental degradation, in which sponges had been hunted so much that they were nearly non-existent near shore, pushing divers further and further out to sea to collect the coveted commodities. The dangers of diving deeper and deeper mark the central conflict of the film. After the deadly reef claims his father, our hero becomes more determined to make the dive and claim the sponges that lie at the bottom, no matter what dangers await him.

The film certainly looks great, the Technicolor and CinemaScope mix really pops, especially on the new Twilight Time Blu-Ray, but it's all in service of a paper-thin plot, blandly executed by Robert Wagner and Terry Moore's dull leads; a pair that lacks any semblance of chemistry whatsoever. But they're pretty, just like the underwater photography, which makes Beneath the 12-Mile Reef little more than an experiment to show off the new CinemaScope technology. Attractive leads + pretty scenery = something Fox could use to showcase their new "see it without glasses" answer to 3D and the growing threat of television. It's a historical curiosity now, but unfortunately its story doesn't really live up to the CinemaScope grandeur.

GRADE - ★½ (out of four)

HOUR OF THE GUN (1967, Twilight Time)

John Sturges revisits the story of his own 1957 film, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral 10 years later in Hour of the Gun, a film that subverts the myth of that legendary battle and examines its moral ramifications, as well as the toll it took on its participants. Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, here portrayed by James Garner and Jason Robards, aren't so much heroes here as men caught in a morally dubious family feud with the traditionally villainous Clantons. The iconic gunfight is quick and nasty, leading to Earp's Captain Ahab-esque quest for revenge against the Clanton clan.

Hour of the Gun upends the glamorous mythology of the American west, and shows us the ugly underbelly that isn't quite as cut-and-dried as our legends would have us believe. While the film loses steam in its second half, it remains a fascinating study of American myth-making. It shows the Old West as a lawless frontier, where even the "good guys" are flawed and fallible. It's much more about the consequences of violence than it is the violence itself, presaging the revisionist westerns of the late 60s and 70s like The Wild Bunch and Lawman (also a recent Twilight Time release). Sturges has the guts to confront a myth he helped perpetuate 10 years earlier in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and examines the effects of its morally questionable violence on the men who helped perpetrate it.

GRADE - ★★★ (out of four)

KILL BABY, KILL! (1966, Kino Lorber)

Mario Bava was perhaps one of the greatest horror aestheticians of all time. Even in a weaker film like Kill Baby, Kill, Bava still dazzles with his visual prowess and evocative sense of time and place. Here, he introduces us to a tiny Victorian-era village that is plagued by a curse wrought upon them after the death of a young girl decades before, who returns from the grave to compel those who wronged her family to commit suicide.

Not as graphic as some giallo horror, Kill Baby, Kill is more of an atmospheric ghost story; all Gothic architecture and fog. It takes a while for anything to really start happening, which is typical of giallo; they often failed to live up to their lurid premises. But Bava was more of an artist than a smut peddler, and he uses suggestion to his advantage here, telling a classic ghost story with spooky flair. Taking cues from such disparate inspirations as Cocteau's La Belle et la Bete and Powell and Pressburger's Black Narcissus, Bava creates a chilling tale with a painter's eye. The brightly colored lighting, the elaborate sets, the striking cinematography, it all adds up to something more than its simple plot. Bava made stronger films with stronger thematic content, but Kill Baby, Kill is an undeniably beautiful entry in the director's canon, marking perhaps one of his most stunning visual achievements, turning classical horror into something akin to poetry.

GRADE - ★★½ (out of four)

TITANIC (1943, Kino Lorber)

Made in Germany in 1943, Herbert Selpin’s Titanic was conceived by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels himself as an anti-British propaganda piece, laying the blame for the disaster at the feet of British greed. While human arrogance certainly played a part in the sinking, Selpin and Goebbels imagine a battle for control of the White Star Line between Bruce Ismay and John Jacob Astor, the former pushing Captain Smith to race to New York in order to set a world record win the Blue Ribband (never a realistic goal for the real Titanic) in order to drive up stock prices, the latter trying to drive White Star stock prices down in order to buy a majority share and take over the company. They even go so far as to make up a completely fictional German officer who is the only honorable person in the film to stand up to the rampant avarice on display.

The problem for the film was that Germans were on a figurative Titanic of their own in 1943, and it was never released for fear that the scenes of mass panic would demoralize audiences. Not to mention the fact that the irony of accusing Britain of naked thirst for power seemed to have been completely lost of Goebbels. Even so, during production, Selpin was arrested by the Gestapo and the film was taken over by an uncredited Werner Klinger (Selpin was found dead in his cell the day after his arrest). It’s unfortunate that Titanic is filled with such blatant and often disgusting propaganda (its slander of real people is unconscionable), because it also has some genuinely affecting scenes, and the special effects are top-notch for the time. In fact, since the film was never actually released in complete form, some of the visual effects shots were recycled for Roy Ward Baker’s 1958 film, A Night to Remember.

Excise the cringe-inducing anti-British sentiment, and Titanic is actually a largely effective (if often historically inaccurate) disaster film. But it’s hard to separate the film from its troubling legacy and connection to Nazi Germany. It’s surprisingly fact-based at times, complete nonsense at others, yet ultimately inextricable from the evil regime that created it, making it a fascinating case study in how propaganda bends facts to suit its own agenda.

GRADE - ★★ (out of four)

Robert D. Webb's Beneath the 12-Mile Reef was either the second or third filmed shot in CinemaScope, depending on who you ask. Either way, this early widescreen film was a hit for 20th Century Fox, most likely because of the novelty of its cinematography. The film itself is a bit of a slog, a dry Romeo & Juliet riff set amid two warring families of sponge-divers. Who knew that the world of sponge-diving was so cutthroat?

It's interesting that even in 1953, there were themes of environmental degradation, in which sponges had been hunted so much that they were nearly non-existent near shore, pushing divers further and further out to sea to collect the coveted commodities. The dangers of diving deeper and deeper mark the central conflict of the film. After the deadly reef claims his father, our hero becomes more determined to make the dive and claim the sponges that lie at the bottom, no matter what dangers await him.

The film certainly looks great, the Technicolor and CinemaScope mix really pops, especially on the new Twilight Time Blu-Ray, but it's all in service of a paper-thin plot, blandly executed by Robert Wagner and Terry Moore's dull leads; a pair that lacks any semblance of chemistry whatsoever. But they're pretty, just like the underwater photography, which makes Beneath the 12-Mile Reef little more than an experiment to show off the new CinemaScope technology. Attractive leads + pretty scenery = something Fox could use to showcase their new "see it without glasses" answer to 3D and the growing threat of television. It's a historical curiosity now, but unfortunately its story doesn't really live up to the CinemaScope grandeur.

GRADE - ★½ (out of four)

HOUR OF THE GUN (1967, Twilight Time)

John Sturges revisits the story of his own 1957 film, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral 10 years later in Hour of the Gun, a film that subverts the myth of that legendary battle and examines its moral ramifications, as well as the toll it took on its participants. Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, here portrayed by James Garner and Jason Robards, aren't so much heroes here as men caught in a morally dubious family feud with the traditionally villainous Clantons. The iconic gunfight is quick and nasty, leading to Earp's Captain Ahab-esque quest for revenge against the Clanton clan.

Hour of the Gun upends the glamorous mythology of the American west, and shows us the ugly underbelly that isn't quite as cut-and-dried as our legends would have us believe. While the film loses steam in its second half, it remains a fascinating study of American myth-making. It shows the Old West as a lawless frontier, where even the "good guys" are flawed and fallible. It's much more about the consequences of violence than it is the violence itself, presaging the revisionist westerns of the late 60s and 70s like The Wild Bunch and Lawman (also a recent Twilight Time release). Sturges has the guts to confront a myth he helped perpetuate 10 years earlier in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and examines the effects of its morally questionable violence on the men who helped perpetrate it.

GRADE - ★★★ (out of four)

KILL BABY, KILL! (1966, Kino Lorber)

Mario Bava was perhaps one of the greatest horror aestheticians of all time. Even in a weaker film like Kill Baby, Kill, Bava still dazzles with his visual prowess and evocative sense of time and place. Here, he introduces us to a tiny Victorian-era village that is plagued by a curse wrought upon them after the death of a young girl decades before, who returns from the grave to compel those who wronged her family to commit suicide.

Not as graphic as some giallo horror, Kill Baby, Kill is more of an atmospheric ghost story; all Gothic architecture and fog. It takes a while for anything to really start happening, which is typical of giallo; they often failed to live up to their lurid premises. But Bava was more of an artist than a smut peddler, and he uses suggestion to his advantage here, telling a classic ghost story with spooky flair. Taking cues from such disparate inspirations as Cocteau's La Belle et la Bete and Powell and Pressburger's Black Narcissus, Bava creates a chilling tale with a painter's eye. The brightly colored lighting, the elaborate sets, the striking cinematography, it all adds up to something more than its simple plot. Bava made stronger films with stronger thematic content, but Kill Baby, Kill is an undeniably beautiful entry in the director's canon, marking perhaps one of his most stunning visual achievements, turning classical horror into something akin to poetry.

GRADE - ★★½ (out of four)

TITANIC (1943, Kino Lorber)

Made in Germany in 1943, Herbert Selpin’s Titanic was conceived by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels himself as an anti-British propaganda piece, laying the blame for the disaster at the feet of British greed. While human arrogance certainly played a part in the sinking, Selpin and Goebbels imagine a battle for control of the White Star Line between Bruce Ismay and John Jacob Astor, the former pushing Captain Smith to race to New York in order to set a world record win the Blue Ribband (never a realistic goal for the real Titanic) in order to drive up stock prices, the latter trying to drive White Star stock prices down in order to buy a majority share and take over the company. They even go so far as to make up a completely fictional German officer who is the only honorable person in the film to stand up to the rampant avarice on display.

The problem for the film was that Germans were on a figurative Titanic of their own in 1943, and it was never released for fear that the scenes of mass panic would demoralize audiences. Not to mention the fact that the irony of accusing Britain of naked thirst for power seemed to have been completely lost of Goebbels. Even so, during production, Selpin was arrested by the Gestapo and the film was taken over by an uncredited Werner Klinger (Selpin was found dead in his cell the day after his arrest). It’s unfortunate that Titanic is filled with such blatant and often disgusting propaganda (its slander of real people is unconscionable), because it also has some genuinely affecting scenes, and the special effects are top-notch for the time. In fact, since the film was never actually released in complete form, some of the visual effects shots were recycled for Roy Ward Baker’s 1958 film, A Night to Remember.

Excise the cringe-inducing anti-British sentiment, and Titanic is actually a largely effective (if often historically inaccurate) disaster film. But it’s hard to separate the film from its troubling legacy and connection to Nazi Germany. It’s surprisingly fact-based at times, complete nonsense at others, yet ultimately inextricable from the evil regime that created it, making it a fascinating case study in how propaganda bends facts to suit its own agenda.

GRADE - ★★ (out of four)

Comments