From the Repertory - 1/23/17

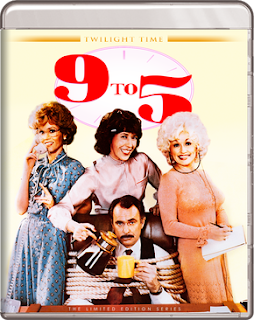

9 TO 5 (Twilight Time)

Three women fantasize about getting revenge on their sexist pig of a boss, only to accidentally find themselves getting actual revenge. Lily Tomlin, Jane Fonda, and Dolly Parton make a fantastic team (and Dolly's title tune is one of her most infectious works). In fact their chemistry is so terrific it's easy to forgive the film's occasional faults and lulls in pacing. There's something remarkably progressive about a Reagan-era comedy being so pointedly feminist, but it's also a little depressing seeing just how much of it remains timely even 36 years later.

GRADE - ★★★ (out of four)

BLACK GIRL (The Criterion Collection)

Ousmane Sembene's feature debut, Black Girl (La Noire De...), put African cinema on the map in 1966, introducing the world to an often neglected and misunderstood continent. Sembene told storied from an African perspective in a way that European and American audiences had never seen, and the thematic core of Black Girl is a shocking jolt to the system.

Based on one of Sembene's own short stories, Black Girl follows Diouana (the striking Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a Senegalese seamstress who takes a job for a white French family, and heads back to France with them to take care of their children. She soon discovers, however, that the family and their friends views her as more of an exotic curiosity than a person, and that the job isn't the job she thought she was accepting. Hundreds of miles away from home, in a foreign country, and trapped in the drudgery of a maid's life, she begins to slip further and further into depression.

Sembene's direction is sparse, anchored by Diouana's inner musings, and scored with music so incongruously upbeat that it almost becomes grating (I was reminded of Djibril Diop Mambéty's Touki Bouki, for which Black Girl was a likely inspiration, and its use of "Paris, Paris"). Yet it wisely makes the audience feel as alienated from its surroundings as Diouana. Sembene himself was a product of colonialism, having grown up in French Senegal, and Black Girl is a stinging condemnation of its effect on every day African citizens. It's all symbolized by the mask that Diouana presents to her employer after she is hired, which becomes the mask all Africans are forced to wear in the presence of white people. Here, Sembene forcefully reclaims that African identity by tearing away the mask, both figuratively and literally (in the film's haunting final shot). He would go on to make stronger films, but in the course of only an hour, Black Girl announced to the world that Africa would be silent no more. And the results were both groundbreaking and deeply moving.

The Criterion Blu-Ray also includes Sembene's debut short film, Borom Sarrett (The Waggoner). Sembene may have gone to film school in the Soviet Union, but his directorial style more resembles Italian Neorealism and the films of Vittorio De Sica. Yet the social realism that informs his debut film, Borom Sarrett is distinctly Soviet, with its focus on the plight of the common man, and his desire to rise above his station and take his place among the bourgeoise, even at the expense of fellow proletarians.

Borom Sarrett follows the day in the life of a cart driver in Senegal as he carries his passengers to and from their destination. Beggars ask him for money, rich passengers abuse him, and all the while he enslaves himself in order to put food on his family's table each day, if he's even able to do that. Many of the techniques that Sembene uses here would reappear in his 1966 debut feature, BLACK GIRL, but it was Borom Sarrett that first heralded the arrival of a powerful voice in cinema, one who would lend that voice to people who had yet to be heard.

Available 1/24/17 from The Criterion Collection.

GRADE - ★★★½ (out of four)

STARDUST MEMORIES (Twilight Time)

Woody Allen channels Federico Fellini (with just a dash of Preston Sturges) in this disarmingly probing riff on 8 1/2, which follows a filmmaker's quest for meaning at a retrospective of his own work, opening a window into the inspirations for each of his films. Allen's meta-textual musings are as fascinating as they are funny, diving not only into the character's psyche, but Allen's own as well. The director's trademark neuroses have arguably never felt so natural as they do here, as Allen explores their sources both through the films he makes and the stories that inspired them.

He also plays a filmmaker known for making lighthearted comedies, who wants to be taken seriously by making dramatic, experimental films. In the process, he ends up making a more personal, philosophical film while maintaining his own unique sense of humor. That's part of what makes Stardust Memories so remarkable. This is Allen exploring his own artistic identity. And while he may borrow heavily from Fellini to do it (the whole style of the film has a very 1960's European art-house feel), with the aid of cinematographer Gordon Willis and the peerless Charlotte Rampling as his female lead, Allen dives deeper into his own persona than in any of his films before or sense. Rampling's long take, in which Allen holds the camera in medium close-up as she goes through an entire spectrum of emotions, might be the single most stunning shot in any Allen film.

GRADE - ★★★½ (out of four)

Three women fantasize about getting revenge on their sexist pig of a boss, only to accidentally find themselves getting actual revenge. Lily Tomlin, Jane Fonda, and Dolly Parton make a fantastic team (and Dolly's title tune is one of her most infectious works). In fact their chemistry is so terrific it's easy to forgive the film's occasional faults and lulls in pacing. There's something remarkably progressive about a Reagan-era comedy being so pointedly feminist, but it's also a little depressing seeing just how much of it remains timely even 36 years later.

GRADE - ★★★ (out of four)

BLACK GIRL (The Criterion Collection)

Ousmane Sembene's feature debut, Black Girl (La Noire De...), put African cinema on the map in 1966, introducing the world to an often neglected and misunderstood continent. Sembene told storied from an African perspective in a way that European and American audiences had never seen, and the thematic core of Black Girl is a shocking jolt to the system.

Based on one of Sembene's own short stories, Black Girl follows Diouana (the striking Mbissine Thérèse Diop), a Senegalese seamstress who takes a job for a white French family, and heads back to France with them to take care of their children. She soon discovers, however, that the family and their friends views her as more of an exotic curiosity than a person, and that the job isn't the job she thought she was accepting. Hundreds of miles away from home, in a foreign country, and trapped in the drudgery of a maid's life, she begins to slip further and further into depression.

Sembene's direction is sparse, anchored by Diouana's inner musings, and scored with music so incongruously upbeat that it almost becomes grating (I was reminded of Djibril Diop Mambéty's Touki Bouki, for which Black Girl was a likely inspiration, and its use of "Paris, Paris"). Yet it wisely makes the audience feel as alienated from its surroundings as Diouana. Sembene himself was a product of colonialism, having grown up in French Senegal, and Black Girl is a stinging condemnation of its effect on every day African citizens. It's all symbolized by the mask that Diouana presents to her employer after she is hired, which becomes the mask all Africans are forced to wear in the presence of white people. Here, Sembene forcefully reclaims that African identity by tearing away the mask, both figuratively and literally (in the film's haunting final shot). He would go on to make stronger films, but in the course of only an hour, Black Girl announced to the world that Africa would be silent no more. And the results were both groundbreaking and deeply moving.

The Criterion Blu-Ray also includes Sembene's debut short film, Borom Sarrett (The Waggoner). Sembene may have gone to film school in the Soviet Union, but his directorial style more resembles Italian Neorealism and the films of Vittorio De Sica. Yet the social realism that informs his debut film, Borom Sarrett is distinctly Soviet, with its focus on the plight of the common man, and his desire to rise above his station and take his place among the bourgeoise, even at the expense of fellow proletarians.

Borom Sarrett follows the day in the life of a cart driver in Senegal as he carries his passengers to and from their destination. Beggars ask him for money, rich passengers abuse him, and all the while he enslaves himself in order to put food on his family's table each day, if he's even able to do that. Many of the techniques that Sembene uses here would reappear in his 1966 debut feature, BLACK GIRL, but it was Borom Sarrett that first heralded the arrival of a powerful voice in cinema, one who would lend that voice to people who had yet to be heard.

Available 1/24/17 from The Criterion Collection.

GRADE - ★★★½ (out of four)

STARDUST MEMORIES (Twilight Time)

Woody Allen channels Federico Fellini (with just a dash of Preston Sturges) in this disarmingly probing riff on 8 1/2, which follows a filmmaker's quest for meaning at a retrospective of his own work, opening a window into the inspirations for each of his films. Allen's meta-textual musings are as fascinating as they are funny, diving not only into the character's psyche, but Allen's own as well. The director's trademark neuroses have arguably never felt so natural as they do here, as Allen explores their sources both through the films he makes and the stories that inspired them.

He also plays a filmmaker known for making lighthearted comedies, who wants to be taken seriously by making dramatic, experimental films. In the process, he ends up making a more personal, philosophical film while maintaining his own unique sense of humor. That's part of what makes Stardust Memories so remarkable. This is Allen exploring his own artistic identity. And while he may borrow heavily from Fellini to do it (the whole style of the film has a very 1960's European art-house feel), with the aid of cinematographer Gordon Willis and the peerless Charlotte Rampling as his female lead, Allen dives deeper into his own persona than in any of his films before or sense. Rampling's long take, in which Allen holds the camera in medium close-up as she goes through an entire spectrum of emotions, might be the single most stunning shot in any Allen film.

GRADE - ★★★½ (out of four)

Comments